Introduction

PowerPoint makes us stupid

General James N. Mattis

When leaders in organisations present new strategic initiatives, I often get dissapointed by what I could call ‘shallow’ or ‘superficial communication.

Maybe I share the frustration of General James N. Mattis, a retired United States Marine Corps general and former U.S. Secretary of Defense. He made the remark quoted above, during his time as a commander, criticizing the over-reliance on PowerPoint presentations in the military.

I Observe multiple challenges in the organisations that I have worked for.

- Leaders are only communicating a power-pointy, superficial, high level strategy.

- Lack of prioritisation

- The organisation do alot of poorly coordinated goal setting but lacks a coherent strategy.

- The organisation implements a copy/pasted process, with insufficeint analysis of the current context of the organisation.

- Following the rituals of a process or tool, while forgetting the real goal.

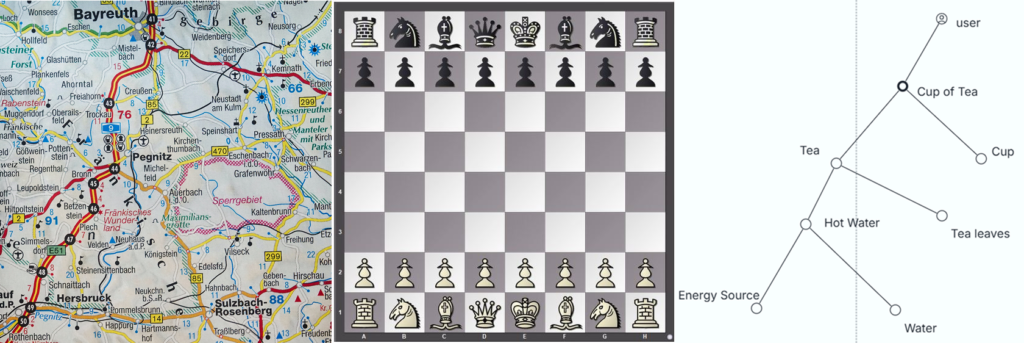

I Think Simon Wardley nails the problem of over simplification when he talks about the two why’s in strategy. The ‘Why of Purpose’ and the ‘Why of movement’. In a game of chess the ‘why of purpose’ is to checkmate the king of your opponent. This is easy to communicate. The ‘why of movement’ in chess would be why move one piece ower another. This ‘Why’ requires much more elaborate explanation, but is essential to understand in order to win in chess.

Leaders tend to only present the why of purpose but skip over the why of movement. I understand that short and simple communication is warranted. But when its not followed by deeper explanation that bring clarity to, what each individual in the organisation should do, or what it actually takes to achieve the why of purpose then we have a problem. While the Why of purpose gives direction it doesn’t tell us how to get there.

Simon Wardley claims, that its much more easy to go some where if we have a map.

Wardley map quick recap

I will assume that you allready know this. Rather than duplicating numerous introductions to the subject.

For another article explaining the basics please take a look here.

For a quick reference check this 1:30 minutes video by Ben Mosior here

or a 9 minute video by the inventor of Wardley maps Simon Wardley here

But let us at least briefly remind our selves of some key warldey mapping concepts

- A Wardley map is a map of a value-chain.

- The X axis represent evolution of components (how evolved is a component)

- The Y axis represent how visible components are relative to the user.

- We use the strategy cycle to ask questions about the map

- In the strategy cycle we have the 5 Tzun Zu factors (from the art of war)

- Purpose

- Landscape

- Climate

- Doctrine

- Leadership

- The strategy cycle is also known as the ooda loop.

What is a Strategy?

In the following I will try to explain how the concepts in the strategy definition defined by Richard Rumelt in “Good Strategy, Bad Strategy” can be related to concepts in Wardley mapping.

Rumelt divides a kernel strategy in to three essentiel components addressing a challenge:

- Challenge *

- Diagnosis

- Guiding Policies

- Coherent Actions

The Challenge

A Strategy must solve some concrete challenge. Rallying around solving concrete challenges will give your strategy direction and focus. If you just do goal setting like increasing revenenue by 10 % the next year, then you have achived little. This dosen’t tell you anything about what the challenge is or how you will reach your goal. Rumelt offers deeper explanation and examples of this in “Good Strategy, Bad Strategy”.

In relation to wardley mapping the idea of purpose is a kind of challenge. But another way to look at challenge comes from theories of constraints. If we can identify the essential or most important constraint in our system or value chain, then we can say that we have identified a challenge or the challenge we want to address. Tristan Slominski has an excelent tutorial where he explains how to map constraints in a wardley map. He also explains different kinds of constraints like constraints in User, User need or component in a wardley map. So use Wardley maps to:

- Communicate purpose by placing the Users and userneeds of the value chain in the Warldey map

- Focus on components of the value chain where the main constraints for value are present.

- Visualise inertia that block evolution towards a better state of those components.

- Visualise intent by showing what components we want to evolve.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis sounds very much like being at the doctor. And this is actually a usefull analogy. Often when going to the doctor you have a very concrete problem or challenge. The doctor will ask you questions, examine you and try to make a diagnosis. If the doctor just resort to general actions to take, like drinking more water, eating more healthy or just ordinate pain killlers you might get disappointet. While these advices might be of general value you don’t feel that the doctor has taken you serious or actually determined what your exact problem is. What I am trying to communicate here is that you might actually suffer from a more rare syndrom that can not just be cured by drinking more water. The same goes for business strategies. Often we just treat our situation as generic and thus we try to mimic what every one else does. We should instead start examining our own situation and come up with a diagnosis of the specific challenges we are facing.

In relation to wardley mapping concepts like situational awareness and drawing a map of our situation and context is a form of diagnosis. So use Warldey maps by:

- Visualising the current landscape of the product or the organisation

- Discussing how evolved the components in our value chain are? Do we agree ?

- iterating the Wardley doctrines to evaluate the current state of the organisation

- picking relevant warldey climatic patterns to evaluate if/then scenarios.

Guiding Policies

Guiding policies are needed to help us make decisions. Having identified the challenge we want to do something about and having done a proper diagnosis, we need to move toward something concrete in the form of coherent actions.

Guiding policies tries to constrain our options in order not to get lost in endeless analysis and opportunities. In relation to warldey mapping concepts like doctrine and climatic patterns, yet again ,spring to mind as examples of guiding policies. So use Warldey maps by:

- applying Wardley doctrines as guiding policies

- applying Wardley climatic patterns as guiding policies

- discussing priority of movement of value chain components to an evolved state.

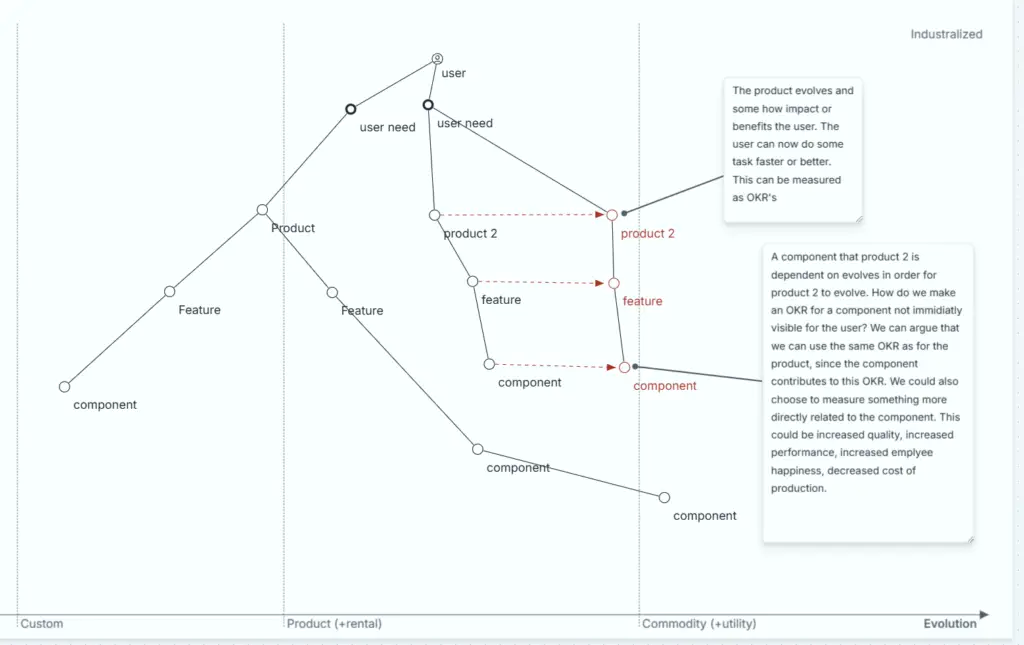

Coherent Actions

Coherent Actions are concrete actions that are, well yes, coherent. Well that sounded like a circular explanation. What we want to emphasis here is that actions are something tangible as opposted to abstract or generic. By using the word ‘coherent’ we want to emphasise that the actions should work together and point in the same direction. In chess we could say that moving the pieces are actions, and if the movements support each other, they are coherent. We don’t want actions that are uncoherent. In chess, victory lies not in isolated brilliance but in the coordinated harmony of every move. Each piece must work in concert with the others, to create pressure, exploit weaknesses, and deliver decisive impact. The board is a battlefield of interdependence, where the true power of a move is realized only when it supports the broader strategy. In Warldey mapping we can relate more technical and hidden value chain components out of sight for the user and management all thet way up to the user needs. So use Warldey maps by:

- Visualising and commuinicating how dependencies contribute to serving user needs, by following the relations between components all the way up to the user needs.

- Visualising and Prioritising what component we focus on in order to evolve our services to satisfy users.

- Visualising how movements of components in the map points in a coherent strategic direction.

- Ask yourself if any thing are contradictory. A map should give you a better chance at spotting that.

Addressing observed challenges with Rumelt and Wardley

Hopefully by now we have sufficient understanding of the 3 elements in Rumelts strategy kernel addressing an articulated challenge for the organisation. We can continue to addresing the 5 observed problems.

Lets address Point 1 from above.

“Leaders are only communicating a power pointy superficial high level strategy.”

“The organisation implements a copy/pasted process, with insufficeint analysis of the current context of the organisation.” and “Following the rituals of a process or tool, while forgetting the real goal.”

A Conceptual wardley map where we could put OKR’s on components in the value chain.

“Lack of prioritisation” and “The organisation do alot of poorly coordinated goal setting but lacks a coherent strategy”.

of their interactions.” “

How Strategy by Comity Leads to Incoherent Actions

- Conflicting Goals: When multiple stakeholders have differing priorities, the resulting strategy may attempt to address all of them, even if they are contradictory.

- Example: An organization might simultaneously pursue cost-cutting (efficiency) and extensive market expansion (growth), leading to resource conflicts.

- Scattered Efforts: Without a clear focus, resources and efforts are spread thin, making it hard to achieve any meaningful progress on a single goal.

- Lack of Synergy: Actions taken under strategy by comity often lack the interdependence and reinforcement necessary for a coherent strategy.

- Reactionary Decisions: Instead of proactive, aligned actions, decisions are made in response to external pressures or to satisfy internal factions, undermining long-term strategic goals.

Mitigating Incoherence in Strategy by Comity

How do we then avoid the mistakes just mentioned?

- Establish a clear guiding policy to ensure all actions align with the same strategic objective.

- Use Rumelt’s kernel of strategy to identify trade-offs and prioritize.

- Ensure leadership enforces discipline in decision-making to avoid the temptation of appeasing every stakeholder at the expense of coherence.

Goal setting is not a strategy!

In Good Strategy Bad Strategy, Richard Rumelt critiques the common practice of goal-setting, particularly when it becomes disconnected from actionable strategies. According to Rumelt, the problem lies in:

Substituting Goals for Strategy:

- Organizations often mistake setting ambitious goals (e.g., “double revenue in two years”) for developing a strategy. Goals describe desired outcomes but do not address how to achieve them.

Lack of Actionable Steps:

- Goal-setting without identifying clear, coordinated actions is ineffective. A real strategy includes actionable steps tailored to overcome challenges and leverage opportunities.

Ignoring the Problem:

- Effective strategy starts with diagnosing the core problem. Rumelt emphasizes that many organizations skip this step, setting goals without understanding the barriers or addressing the root causes.

Overreliance on Aspirational Language:

- Lofty, vague goals like “becoming the industry leader” are common but offer no guidance. Rumelt warns against confusing vision statements or wishful thinking with strategy.

The “Template Thinking” Trap:

- Many organizations use boilerplate processes for goal-setting, resulting in generic objectives that fail to address specific circumstances or challenges.

Key Takeaway:

Rumelt argues that meaningful progress comes from a well-crafted strategy, not from setting ambitious goals alone. A good strategy is rooted in a clear diagnosis of the problem, a guiding policy, and coherent actions, while mere goal-setting often bypasses these critical components. I Will add that you can use Wardley maps to support formulating your strategy kernel.